The sole point of interest here is the head-scratcher

question of how a group of scraggly, skeevy, second-tier country-rockers

managed to convince Stevie Wonder to take time off from his astonishing run of

1970s albums to sit in on piano for an inert rendition of his own “She’s a

Sailor.” Otherwise, it’s modest, unremarkable stuff through and through. The

Byrds presence has doubled from the last LP; Gene Parsons is now joined by Skip

Battin, meaning the Burrito Bros have now perversely replicated the earlier

band’s personnel shifts of the last decade, with the Hillman/Gram

Parsons/Clarke lineup giving way to the late-Byrds rhythm section—and the accompanying decline in quality. I suspect this also

speaks to the insularity of the mid-decade country-rock scene; apparently Richie Furay was busy this year. But it’s all harmless

enough, and they seem to be having fun, so it’s as difficult to resent this as

it is to remember it ten minutes later.

Sunday, March 31, 2013

Saturday, March 30, 2013

The Byrds, Mr. Tambourine Man (1965)

However obvious it sounds in retrospect, the fusing of Dylan

and the Beatles was modern rock’s Cartesian moment (and for what it’s worth, cogito, ergo sum seemed pretty

self-evident after the fact too). The LP never sounds like an historical

artifact, either—forty years after the fact, it still exudes an uncontainable energy. So many

genealogies begin here; McGuinn’s jangling guitar bequeathed Peter Buck and indie rock as we know it, and even

Michael Clarke, never the world’s greatest drummer, brings a striking visual

cool, all t-shirts and eyes buried under hair and sullen lips, looking like

nothing so much as a young Thurston Moore.

The real secret genius, though, is Gene Clark; any band can

cover Dylan, but few could deliver originals like his. Bashing out one perfect

pop gem after another, he makes it sound easy, so that when the bridge on “You

Won’t Have to Cry” threatens to climb a step into straight-up

wanna-hold-your-hand-ness, it’s possible to read it as a sophisticated joke rather

than aping and have some ground to stand on. Maybe it’s both. Either way, “I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better,” “Here

Without You,” It’s No Use,” etc.: ten of the album’s twelve tracks (and all of

the originals) clock in under three minutes, often well under (Dylan's "Spanish Harlem Incident" was short; theirs is shorter by 20%, not even two minutes long!), reflecting an intuitive awareness of pop mechanics at

their finest; crawl into the ear, get out quick, and leave a lasting earworm. Every single Clark composition is A-side material, every single cover an assertive act of ownership. The American rock LP nearly peaked here, at its birth.

Friday, March 29, 2013

Graham Nash/David Crosby (1972)

One of the bigger shocks of my recent vinyl-digging

adventures has been the resolute mediocrity of Graham Nash’s solo work; I have

such positive Hollies associations in my head that I expected more than his

trite and fairly tuneless solitary efforts. At least he writes actual songs

here, with a few, like opener “Southbound Train,” even rising above the moon/June/spoon

template so familiar from his solo LPs. That’s in contrast to Crosby, who

continues to warble idiotic sweet nothings over barren soundscapes that never

once resemble a verse, chorus, melody, or iota of songwriting aptitude, all the

while thinking he’s some sort of countercultural shaman or something. The man’s

utter fraudulence is so risible that I can’t play this without ranting to

anyone nearby, even if it’s just the cats. I'm pretty sure they hate Crosby, too.

Monday, March 25, 2013

The Souther-Hillman-Furay Band (1974)

It had a certain logic: this worked for CSNY. But this name

doesn’t flow as well, and I’m somewhat convinced that’s why it never took off;

it’s neither more grating nor less interesting than your average soft-country

bland-rockers of the era, but “Poco” rolled off the tongue more cleanly (couldn't they at least have gone with some phonetic version, like Shuff?).

Oh, and there's music on the round plastic thing, though to what end? It’s

sad to hear how little Hillman has left to offer—I keep hoping against hope for

another “Have You Seen Her Face,” but no dice. Probably the highlight is when

J.D. Souther’s “Deep, Dark, and Dreamless” almost passes for an Eagles song. That should not be a highlight.

Sunday, March 24, 2013

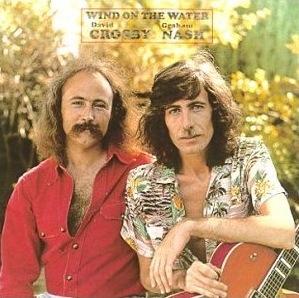

David Crosby and Graham Nash, Wind on the Water (1975)

The relentless crapulence of post-Byrds albums in

general, and the sheer offensiveness of David Crosby’s horrid artistic persona

in particular, have engendered a certain sourness on my part that can slide

into preemptive scorn for these records. So it's through somewhat gritted teeth

that I confess, this album isn’t really half bad. In a rare gesture, Crosby

awakens from his lifelong stupor to kinda, sorta write actual songs, and as

always Nash sounds decent enough as long as you don’t pay more than

half-attention. Nothing sticks out, but nothing grates, and what really proves

the album’s low-intensity non-failure is that two-part closer “To the Last

Whale” somehow manages not to be the abysmal wreck that title very much

demands—but then I also like Star Trek IV and even Yes's "Don't Kill the Whale," so there may be a soft spot here I never realized I had.

Saturday, March 23, 2013

McGuinn, Clark & Hillman (1979)

This must have made sense in 1979: three former Byrds, all

equally washed up artistically and commercially, getting back together for some

of that old magic. It doesn’t happen, of course, though Hillman’s lead track

“Long Long Time” has some power-pop zest all too absent from his other solo

work. I could see the Plimsouls rocking this.

McGuinn and Clark phone their songs in; the only moxie they

bring is in their apparent competition to see who can unbutton his shirt the

furthest on a cover shot, with McGuinn winning at near-belly-button depth. With

a cross-bearing necklace, Clark looks sleazier, though, grizzled and mean like

Rip Torn in Payday, which probably wasn’t far off (his lazy groupie-grabbing

“Backstage Pass” only adds to the image). “Release Me Girl” answers the

question, what would Gene Clark sound like with a disco-lite arrangement, if

anyone was wondering, like some watered-down leftover from No Other, and McGuinn’s closing “Bye Bye, Baby” is fairly lovely if

one can hold awareness of the abysmally insipid lyrics at bay. Otherwise,

nothing to report here.

Oh, there are unfortunately-placed liner notes on the cover

that declare the album has “a timeless quality … that renders analysis

insignificant.” Whoever Stephen Peeples is or was, hopefully he felt shame for

writing that. Which is not to say further analysis would be effort well spent.

Friday, March 22, 2013

Crosby, Stills & Nash (1969)

So pretty, so dumb: killer harmonies saturate the LP, but the

lyrics range from harmlessly mawkish to painful. The whole thing is best

listened to at a slight remove, inattentively; at that level—as lovely sounds

swirling in the background—it’s a near masterpiece. As songs, these are almost pure trash. At least the titular C is

proportionally underrepresented, held to 2.5 songwriting credits of ten tracks;

as always, he strains for profundity and achieves instead gasbagitude. Graham

Nash probably should have been in the Monkees instead and let Mike Nesmith, a far stronger songwriter, take

his role here--but that might not have been fair to Nesmith; not even dealing with Mickey Dolenz could be worse than handling Crosby. Ultimately, this is basically three idiot hippies with nice voices in search of Neil Young.

Thursday, March 21, 2013

Roger McGuinn, Thunderbyrd (1977)

Crap like this is why punk had to happen: tired old dinosaur

rockers flogging the deadest horses since Nietzsche wept, to ever-dwindling

effect. When the highlight of side one is a Peter Frampton cover (it beats the

Tom Petty cover, easily), you’re in trouble. McGuinn has nothing left to say (did he ever?),

co-writes all whopping four originals with Jacques Levy. Not even Neil Young

could probably do much with a song called “Dixie Highway,” and McGuinn/Levy do

far less. Only the closing track, “Russian Hill,” one of those

older/sadder/wiser songs all the 60s survivors seemed to be doing by 1975 or so, even

approaches memorable, and that’s mostly because of the haunted

arrangement, which takes hold almost in spite of McGuinn. Also, that is one hell of a losing streak his solo LP cover art is on, crikes.

Wednesday, March 20, 2013

Skip Battin (1972)

Skip Battin was the Slim Dunlap of the Byrds, joining just

in time to ride out the band’s decline. He wrote a few songs on the final few

albums, often with cinematic themes; nothing too subtle (cf. “Citizen Kane”),

nothing too memorable. I actually like Dunlap’s halfway decent solo albums

more; Battin’s s/t 1972 solo debut is basically akin to the originals a

moderately talented C&W bar band in Topeka plays between covers. The film

stuff continues with “Valentino,” and beats the sports stuff like “The St.

Louis Browns,” but absolutely nothing sticks. All the songs are co-written with

crackpot loony Kim Fowley, but it doesn’t matter; “Captain Video” aspires to

breathless wordsmithery but peaks with “sexual intellectual.”

McGuinn and another Byrd or two show up, but mostly this

reminds me of old novelty flexi-discs like the one my dad used to play for my

mom on her birthday each year, with a thin-voiced singer crooning about coming

from the moon just to sing her a tune. A+ cover art, though.

Tuesday, March 19, 2013

Roger McGuinn, Peace on You (1974)

It’s awkward and unpleasant to see McGuinn so exposed here,

without the rotating cast of talented Byrds to hide behind. Left to his own

devices, he reveals himself an uninspired interpreter of other people’s songs

(and a godawful selector on that front—when the dude’s

not doing Dylan, he seems to think Dan Fogelberg is the next best thing), and

an untalented songwriter with nothing to say and no stylistic flourishes to

conceal the absence. It’s really a sad, dispiriting listen in every way,

checked-out and half-assed and impossible to commit to memory, possibly the

most lifeless thing McGuinn ever did. When that cover art is the best thing about the LP, you know you're in for suffering.

Monday, March 18, 2013

Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, American Dream (1988)

I can’t help assuming these dinosaur rockers, with the

possible exception of the recently incarcerated Crosby, were richer than gods,

so it’s perplexing to hear them record a transparently pointless

paying-the-mortgages record. Usually Young stands out, but this caught him at

the absolute nadir of his most somnolent rut; his tunes do sound marginally

more awake than the perversely titled Life

of the prior year, but that’s an awfully low bar to clear. Crosby, sober but

still insufferable, answers the question, What would Jandek sound like if he

were auto-tuned, and sucked? on the droning “Compass.” When he turns to politics on “Nighttime for the

Generals,” he offers his usual depth of analysis: the CIA, that’s bad. Stills

and Nash each turn in a set of lazy-old-men songs, pleasant enough but utterly

trifling. I will confess an unexpected semi-friendliness toward Stills’s

synth-poppy efforts of the 80s, so concluding with “Night Song” was the right

choice. It’s not good, exactly, but the polished sound holds his usual hippie-bloat

at bay.

The gross, pandering title and shockingly awful cover art

(down to the very font) are somewhat canceled out by the hilarious inside photo

of the three blowhards harmonizing, with a bored or disgusted Young

sitting on a couch looking like he wants to punch them all. It's better than any of the songs.

Saturday, March 16, 2013

Firefall, s/t (1976)

In the soft-rock-sterility songwriting contest between Rick Roberts

and Larry Burnett, we all lose. There’s a faint trace of the core Byrds here,

with Chris Hillman picking up a co-writing credit (with Roberts and Stephen

Stills) on the modestly captivating “It Doesn’t Matter,” but really Michael

Clarke—who mostly does little more than stay in time—is the main link.

According to the back cover, he hasn’t aged too well; his lost years were

apparently not spent at the practice kit. Otherwise it’s so-soft-it-melted rock

all the way through, with songs about love, dolphins, and Cinderella (on the latter of which, Burnett wins some kind of alltime-dick award for shunning a woman he got pregnant and sending her on her way; stay classy, ye gods of MOR FM radio). Props for

burying the big hit single “You Are the Woman” deep on side 2, I guess. I like their later album art more, and arguably the albums too.

Friday, March 15, 2013

The Flying Burrito Bros, Gilded Palace of Sin (1969)

Venerated as this album is, I’ve always found it a little

stiff, too much a formalist exercise. Gram Parsons wholly subjugates Chris

Hillman to his project, but rarely conveys any depth of feeling; “Hot Burrito

#1,” one of the few exceptions, comes too late. Likewise, when the band finally

unclenches on “Hot Burrito #2,” a weight lifts and some actual air seeps in at

last.

Lest this sound harsh, it is, no question, good stuff; ontological status of its authenticity notwithstanding, “Sin City” is simulacra Jean

Baudrillard himself would admire, rockist tropes be damned. But the group is best when it stops feigning

anachronisms and embraces topicality, as on the draft-evading “My Uncle,” which basically sounds like . . . well, the Byrds (although the less said about the closing atrocity “Hippie Boy,” the better).

Thursday, March 14, 2013

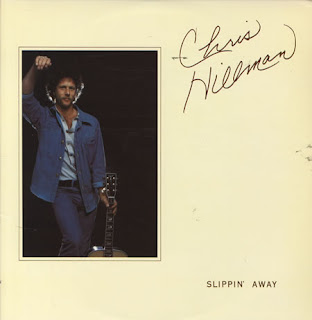

Chris Hillman, Slippin' Away (1976)

For a while, early upon first listening to the Byrds, I thought Chris Hillman was their secret weapon. Turns out that's because I was seduced and deceived by Younger Than Yesterday; his really sharp songwriting more or less began and ended with "Have You Seen Her Face?"

After a post-Byrds decade spent kicking around in various groups, he began his solo career proper here. Is “a more boring Poco” even a legible phrase? It’s the most

accurate description I can devise, and probably more thought than the album

merits; it’s never less, but assuredly never more, than pleasant. There’s a

song called “Take It On the Run” that isn’t that other “Take It On the Run” and

makes one appreciate REO Speedwagon’s pop smarts. There’s a song co-written

with Gram Parsons, which might well have been composed after his passing for

all the presence it contains. And there’s a random bluegrass closer called

“(Take Me In Your) Lifeboat,” which is really all you need to know. Dude is less pompous than David Crosby, is the most glowing comment I can muster.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)