I remain slightly mystified by the Desert Rose Band: how did

Chris Hillman shake off two decades of the doldrums and step into slick Top 40

country-pop so seemingly effortlessly? After years spent mostly coasting

through covers, what reignited his songwriting muse (he had a hand in all but

one track here)? And why are he and fellow old-timer Herb Petersen paired up

with a dude who looks like he should be playing Patrick Swayze’s character in a

Road House sequel?

Whatever questions, or reservations about the style, one may

hold, it would be hard to deny that Hillman & Co. play this game well. Four albums in, the DRB still brings it; no

timeless classics here, but not one dud either, and the whole album flows along

swiftly, aided by nicely constructed melodies and crisp, if time-bound

production (big drum sounds crossed genre lines during this era, it seems).

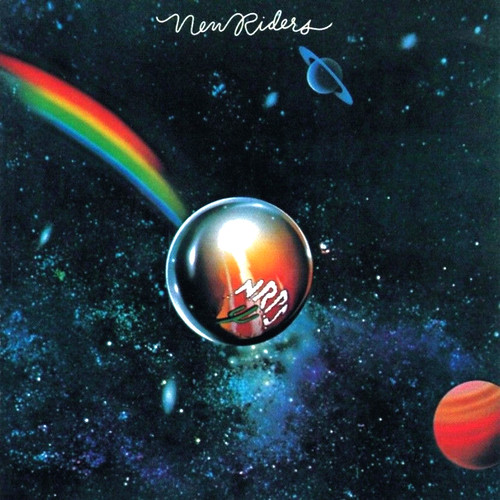

Despite this, and a quite lovely (as always) duet appearance by Alison Krauss, True Love also marked the band's abrupt fall from commercial grace. Perhaps the lackluster title and cringeworthy cover art played a role; for content,

Hillman hadn’t been this on since the

Byrds.