The 1979-80 season must have been a tough one for Larry

Burnett, since he came up with a mere two ditties for this round; subtract one

anomalously jaunty Jock Bartley jam buried safely deep on side 2, and this is

effectively a Rick Roberts auteurist LP. His vision, of a sort of primordial

silky ooze that runs from one song to the next as if discrete units of

songwriting were a thing of the past (or possibly future) is nothing if not

cohesive; this is probably my vote for Firefall’s best, though it manages to

win the dubious honor without a single standout track. “Business is Business,”

a Burnett track declares; indeed: the business here is that of polishing off

every idiosyncratic edge from lyrical content to studio musicianship (the

single proper noun on the entire album is a lone reference to California, and

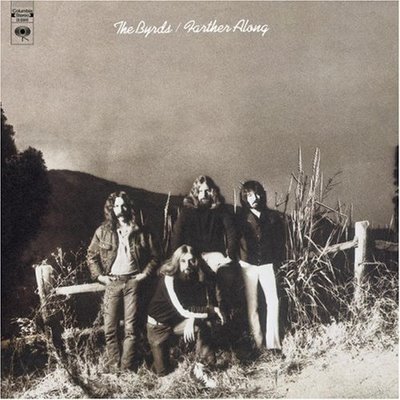

an impersonal one at that). As such, Michael Clarke’s rote 4/4 timekeeping—his

recorded swan song before his revived faux-Byrds touring act and sadly early

death—can almost be read as masterful; no distracting jazz flourishes here,

that’s for sure. Let Steely Dan hire Jeff Porcaro for one verse, an older club

veteran for the next; Clarke in some ways embodies the core of the Firefall

project, all bland and anonymous and easy to listen to, hard to focus on.

That being said, more gripping and harrowing than any percussive work he offered in life was the graphic, grueling letter Clarke offered in death, detailing his alcoholism and warning children not to follow in his footsteps. Undertow has my favorite Firefall cover art, really some of my favorite 70s-malaise imagery altogether, all dark and brooding and ominous and as fuzzy about identity as Friedkin's Cruising (what any of this had to do with their music, I can't tell). But Clarke's visual decline is even more powerful, a sad and stark trajectory from pop heartbreaker to emaciated leftover. RIP to a guy who chanced into a pretty great run of it, and locked into a tragic one at the same time.